The macroeconomic impact of euro area discretionary fiscal policy measures since the start of the pandemic

Prepared by Elena Angelini, Krzysztof Bańkowski, Cristina Checherita-Westphal, Philip Muggenthaler-Gerathewohl and Srečko Zimic

This box provides a model-based analysis of the macroeconomic impact of discretionary fiscal policy measures adopted by euro area governments since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, as reflected in the March 2025 ECB staff projections for the euro area.[1] The analysis investigates the effects of these measures on real GDP growth and inflation, in comparison with a counterfactual scenario of no fiscal policy support as of 2020. It employs two quantitative tools that are regularly used for projections and policy simulations at the ECB: Basic Model Elasticities (BMEs) and the ECB-BASE model.[2] The focus is on the macroeconomic impact of the discretionary fiscal policy measures, which are proxied by the change in the discretionary fiscal policy impulse compared with 2019, the year prior to the pandemic.[3] The box also assesses the impact of support measures introduced by euro area governments since late 2021 in response to the energy crisis and high inflation.[4]

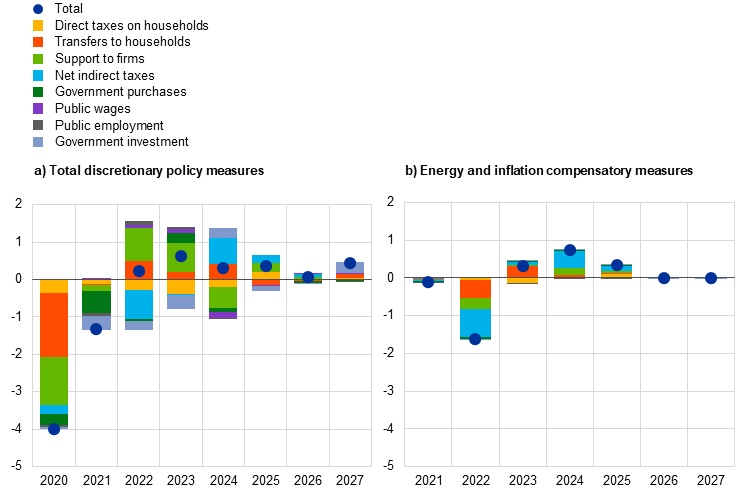

Fiscal policy provided substantial support to the euro area economy to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and the energy crisis. Supportive measures were particularly significant in 2020 and 2021 in response to the pandemic (Chart A, panel a). Governments started to partially withdraw these measures from 2022, which, all else equal, would have resulted in a tightening of fiscal policy. However, at the same time governments provided additional fiscal support in view of the start of the war in Ukraine and the emerging energy crisis (Chart A, panel b). Moreover, further spending was related to refugees, defence and aid to Ukraine. As a result, discretionary fiscal policy in 2022, as assessed by the measures undertaken, was broadly neutral. There was a shift to a fiscal tightening in 2023, as the pandemic support and part of the energy compensatory measures were further unwound. This more than offset a continued increase in public investment, which was mostly funded through the Next Generation EU (NGEU) programme, and a decrease in income taxation, including social security contributions. A further fiscal tightening in 2024 can be attributed primarily to the more substantial unwinding of the energy compensatory measures in that year, which counterbalanced the renewed expansion in government consumption (mainly through purchases of goods and services and transfers in kind). Having risen significantly during the years 2020-2021 to address the pandemic health crisis, government consumption actually fell somewhat over 2022-2023 before rising again in 2024.[5]

Chart A

Discretionary fiscal policy measures since the start of the pandemic and their composition by economic category

(annual changes; percentage of GDP)

Source: ECB/Eurosystem estimates as captured in the March 2025 ECB staff macroeconomic projections.

Notes: Negative (positive) figures denote fiscal loosening (tightening). Discretionary fiscal policy measures follow the “fiscal stance” concept and are expressed as annual changes. Annual measures are expressed as a percentage of nominal potential GDP in the previous year. The chart shows the composition of measures according to the economic channels used in model simulations, as described below.

(i) Subsidies recorded by Eurosystem staff under energy and inflation support are simulated to have a direct impact on energy inflation. Other subsidies are classified as “support to firms” and simulated to improve the operating surplus of companies.

(ii) Capital transfers, which are mainly classified as “support to firms”, are simulated to improve the operating surplus of companies, apart from: (a) the (large) capital transfers funded by the NGEU programme, which support economy-wide investment and are simulated as public investment (see Bańkowski, K. et al., “Four years into NextGenerationEU: what impact on the euro area economy?”, Occasional Paper Series, No 362, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, December 2024); (b) the Italian “Superbonus”, which is simulated to mimic the sizeable, but cyclical (temporary), positive effects on growth stemming from housing investment found in other studies (see, for example, Accetturo, A. et al., “Incentives for dwelling renovations: evidence from a large fiscal programme”, Occasional Papers, No 860, Banca d’Italia, Rome, June 2024, which calculates a fiscal multiplier between 0.7 – with direct effects only – and 0.9 – including indirect effects).

Overall fiscal support is anticipated to remain expansionary during the period 2020-2027, despite the expected scaling-back of discretionary fiscal policy measures over the next few years. Assumed discretionary measures over the projection horizon point to further fiscal tightening (0.9% for 2025-2027). However, when considering the full period 2020-2027, the estimates still point to a significant fiscal loosening (3.3 percentage points of GDP), reflecting the fact that the considerable support provided since the start of the pandemic has only been partially withdrawn. The sustained expansion is primarily attributable to multiple income tax relief measures and broad-based spending increases. This fiscal support has added to the euro area deficit and debt ratios, which are projected to remain well above their pre-pandemic levels in 2027.[6]

Model simulations point to sizeable macroeconomic effects of the discretionary fiscal policy measures since the start of the pandemic, compared with a counterfactual scenario in which these measures were not introduced. The total discretionary fiscal policy measures implemented since 2020 are estimated to have substantially supported real GDP growth over 2020-2022 and to have been broadly neutral or had a somewhat moderating impact on growth thereafter (Chart B, panel a). With regard to inflation as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), the simulations point to a dampening effect in 2022, mainly on account of the energy and inflation compensatory measures that helped to smooth the peak impact of the energy shock. However, they indicate an overall upward impact later on (Chart B, panel b), particularly during the years 2023-2024 when governments started to withdraw the energy price support granted in 2022 and there was a build-up of inflationary pressures resulting from the fiscal stimulus in previous years.[7]

Chart B

Impact of discretionary fiscal policy measures on euro area growth and inflation compared with a counterfactual scenario of no fiscal policy support over 2020-2027

a) Impact of fiscal policy measures on real GDP growth |

b) Impact of fiscal policy measures on HICP inflation |

(annual changes; percentage points) |

(annual changes; percentage points) |

|

|

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: The fiscal “shocks” used in the simulations are as shown in Chart A. The effects on GDP growth and inflation are averages of the results from simulations performed using ECB-BASE and BMEs. Other policies (particularly monetary policy) and factors were kept unchanged in the simulations. More specifically, the ECB-BASE model was simulated with exogenous monetary policies, exchange rates and financial spreads. BME simulations were conducted at individual country level, with macro results aggregated at the euro area level. The standard simulation horizon for BMEs is four years after an initial shock (T+4). No persistency (of the effects on real GDP growth and inflation) is considered in the BME simulations after the year T+4 for a shock originating in year T.

The simulation results are subject to model and data uncertainty, including non-linear and heterogenous behavioural responses of households and firms to the range of fiscal support measures. Sensitivity analyses show that the estimated inflation effects depend strongly on assumptions about the propagation of various fiscal instruments, particularly subsidies, to the macroeconomy, and the extent to which they affect prices (either directly or via firms’ profit margins). Finally, the results shown in this box omit any monetary policy reaction endogenous to the fiscal measures under consideration, in order to isolate the effects of fiscal policy.

Distribution channels: Banking, Finance & Investment Industry

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release